The Tree of Life web project (TOLweb) aims to consolidate phylogenetic information from multitudes of studies in an effort to build a robust tree of all species. It's a great resource, even now as it becomes increasingly clear that no single phylogeny accurately captures species relationships (due to gene flow and horizontal gene transfer).

A user navigates the tree via a web interface with a hierarchical structure, showing the topology of one clade at a time, along with some pretty pictures. However, this is not entirely satisfying, since only a subset of the data can be viewed at a time. For example, viewing the "Eutheria" (the placental mammals), we can see the various families, but we cannot see the genera or species within each one. This format is OK for exploring the tree, but useless to the biologist who wants to "play" with the tree.

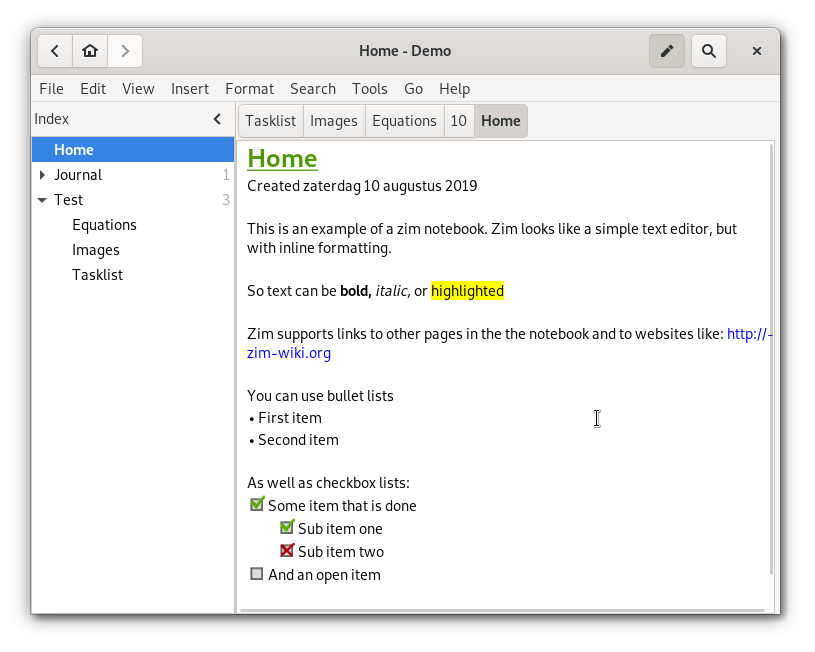

|

| The "Eutheria" page on TOLweb. Clicking on any of the family names would take you to the equivalent page for each family, while clicking on the root would take you up one level (Mammalia). |

The first step is to find the unique TOLweb ID of the clade. Each clade in the tree has a name and a number (NODE ID), which is assigned to the node (branching point) at the root of that clade. For example, node 1 is the root of the tree "Life on Earth", while the Eutheria correspond to node 15997. To find the number corresponding to a clade, simply add this line to the address bar of your web browser:

http://tolweb.org/onlinecontributors/app?service=external&page=xml/GroupSearchService&group=xxx

Where xxx is the name of the clade on tolweb (scientific and common names are usually accepted). This will produce a short XML output with information about this node. Here is the output that was be produced when I specified the clade "primates":

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes"?> <NODES COUNT="1"> <NODE ID="15963"> <NAME><![CDATA[Primates]]></NAME> </NODE> </NODES>

The important bit is the second line, which indicates that this is node 15963. The complete tree corresponding to this clade can then be obtained in one of two ways. TOLweb itself uses an XML format which can be obtained directly by pasting this line into the address bar:

http://tolweb.org/onlinecontributors/app?service=external&page=xml/TreeStructureService&node_id=yyy

Where yyy corresponds to the unique node ID described above. Unfortunately, in my experience, not many programs can read this XML format. But I have found one program that can, and it actually allows you to bypass the above step entirely: Archaeopteryx

Archaeopteryx is a feature-rich java program designed for viewing and manipulating large trees. It's has built-in functionality to retrieve tolweb trees given the node ID.

.png) |

| The primate tree in Archaeoptryx |

Its an ideal program for this kind of thing because it has a great "Dyna Hide" function, whereby it only shows the number of taxon names that can fit on the tree at a given zoom level. Zooming in on a sub-clade then reveals additional names.

|

| Zooming in on the top corner reveals more taxon names |

|

| My own processed and summarized version of the primate tree |