The paper applies two approaches to answering the question of whether eyespots have a single or multiple origin in Nymphalid butterflies, when this trait evolved, and to shed some light on the gene networks involved.

One approach was to plot the presence/absence of eyespots in 399 Nymphalid species (and 21 outgroup species ) onto a previous phylogeny. The distribution of the trait over the tree was used to fit alternative models of single, double or triple origins of the trait, using a Bayesian approach. The authors found that the most consistent model, given the data and the tree, was a single origin of eyespots at the base of the Nympahlidae.

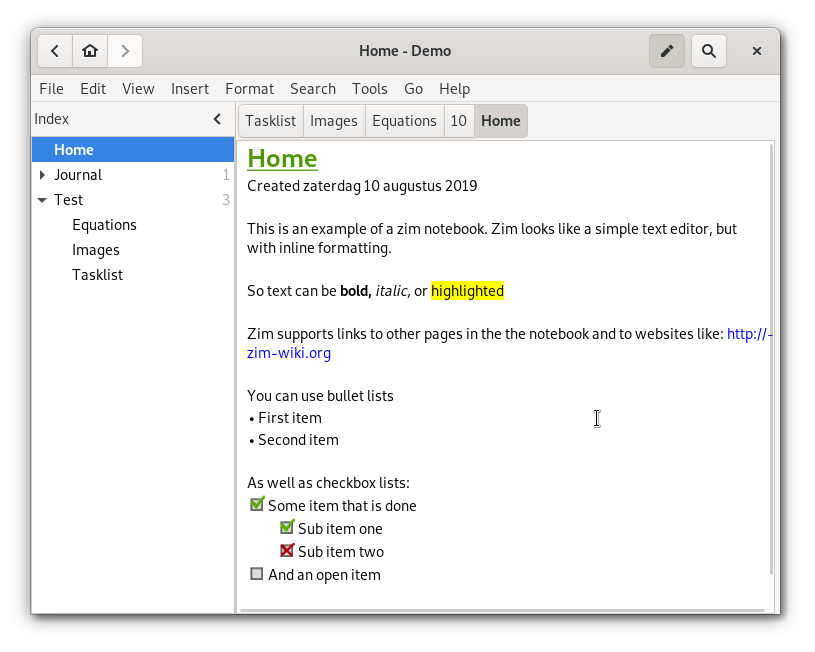

In parallel, the expression data of 5 core developmental genes previously implicated in wing patterning - expression ofthe genes Antennapedia, spalt, engrailed, Distal-less and Notch in eyespot foci were analysed using antibody stains for23 Nymphalid species. The presence or absence of gene expression of each in presumptive eyspot foci was scored and the distribution of trait values across the phylogeny was analysed in a similar way to the presence/absence of eyespots. Their Figure 1 shows a single origin for co-expression of Notch, spalt and Distal-less at the base of the Nymphalidae, but the results for engrailed and Antp were ambigous (the association of these genes with eyespots might have evolved more than once).

The fact that 3 genes together are associated with eyespots at the base of the Nymphalidae is strongly indicative that the network for eyespot pattern was co-opted from a pre-existing role elsewhere in development, a fact re-inforced by the observation that the genes are expressed in a characteristic order (Figure 2):

The fact that 3 genes together are associated with eyespots at the base of the Nymphalidae is strongly indicative that the network for eyespot pattern was co-opted from a pre-existing role elsewhere in development, a fact re-inforced by the observation that the genes are expressed in a characteristic order (Figure 2):All in all, this is a really interesting paper, and a brilliant demonstration that butterflies are a wonderful model system for examining the evolutionary and developmental biology of many complex (and visually striking) traits.